Dante's Inferno: Politics, Scholasticism, and Spiritualty of the High Middle Ages

The context and symbolism behind Dante's inferno

I read Dante’s Inferno for my late medieval history class this last semester, and I struggled a bit to enjoy it. Granted I was pretty academically burnt out by this point but I enjoyed the history and symbolism within the book. In this essay, it is precisely this historical context that I will discuss.

Dante, with Inferno, takes his knowledge of the classical depiction of hell and combines it with Christian doctrine to create a new narrative. This stems from the changing ideas of spirituality arising from the 12th century, as well as scholasticism and the medieval interest in classical texts that often conflicted with the teachings of the church. Throughout Inferno, Dante references the political conflicts that had occurred in the 13th and early 14th centuries, including his own experiences, and argued how these experiences have changed how he sees the world. Throughout Inferno, Dante references the political turmoil between the secular and Papal powers of his time, revealing the new need for a more internal connection to religion, and using scholasticism to challenge the normative ideas of Christian doctrine and society.

Florence in the High Middle Ages was not just an Italian city, but was on track to becoming an independent country in its own right. Florence was a powerhouse of Italy with an army, a flag, its leaders, trade, and coin. As a result of this growing power, internal conflicts were common, especially between the high and low nobility. In 1215, a member of the Buondelmonti family ended a romantic relationship with an Amidei girl abruptly and unkindly, resulting in his murder (xv). Furthermore, the Guelph-Ghibelline factions deriving from the aftermath of the investiture struggle supported opposing sides. The investiture struggle argued whether secular rulers or the pope had the authority to invest in bishops and abbots, essentially, who could choose the bishops and abbots. After the investiture struggle, when the German Emperor Henry V died in 1125 without an heir, the Dukes elected Lothar III of Saxony, while the Hohenstaufens contested for the throne. For the next quarter of a century, a contest for the monarchy ensued with the papacy fueling the flames until Frederick I of the Hohenstaufen family became Emperor in 1152.

The Guelphs supported the papacy and Lothar III, while the Ghibellines supported the Hohenstaufen. The cities that were threatened by the growth of the papal states and papal power typically aligned with the Ghibellines, whereas the cities that wanted freedom from the Empire tended to be Guelph, such as Florence. Frederick I attempted to expand outside of Germany and into Italy; however, one of the Dukes in the German Empire, Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony, led opposition in Germany, while the Papacy led opposition in Italy. In 1176, Frederick I was defeated by the Guelph Lombard League in the Battle of Legnano. Despite this, in 1180, Frederick defeated Henry the Lion, and three years later, he successfully negotiated with the Lombard League. Frederick I managed to engage his son Henry VI to Constance of Sicily, creating an alliance with southern Italy and establishing stability before dying during the Third Crusade. When the heir to the Kingdom of Sicily died, Henry VI became the new King in 1194 to the dismay of the Papacy. The German kingdom now surrounded Rome, and the Papacy greatly opposed this dynamic. After Henry’s death, his infant son became the ward of the papacy.

Under Frederick II’s rule, who had been raised by Pope Innocent III, the feud between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines escalated further. Frederick II focused on Sicily and northern Italy, leading to resistance from the Pope, who excommunicated not only Frederick but also his entire family, which was seen as a major abuse of Papal power. In 1248, Frederick II helped remove the Guelphs who supported the Pope from Florence, with the leader of the Ghibellines, Farinata Uberta, and in 1251, they returned to push the Ghibellines out, only to be defeated again in 1258 (xv). After Frederick II died in 1250 and his heir died only four years later, there was once again a contest for the monarchy with no ruling Emperor that the Papacy fueled until 1312. Amidst this chaos, in 1260, the Ghibellines massacred the Guelphs at Montaperti, killing six thousand and capturing sixteen thousand (xv). In 1266, the Guelphs returned and finally wiped out the Ghibellines at Benevento (xv).

Dante Alighieri, mainly referred to as just Dante, was born in 1265 to a family of lesser nobility just a year before the Guelphs finally defeated the Ghibellines (xvi). Dante became an orphan early in his life but received a good education that fit his social status. It is, however, believed that Dante may have also been mainly self-taught, taking an interest in classical history and philosophy, as was popular due to scholasticism. One of Dante’s idols was Virgil, a famous Roman poet who, in Inferno, became Dante’s guide through hell. In 1289, at 24 years old, Dante was engaged in the Battle of Campaldino, and in 1295, he appears to have been active in politics (xvii). By 1299, Dante had advanced to a minor ambassadorship, and in 1300, conflict erupted once again in Florence when the “white” and “black” parties arose after a murder. The White party supported the independence of city-states, still supporting the papacy, but opposed what they saw as excessive papal influence on Italian city-states. The Blacks, however, supported the papacy. In 1300, Dante was elected as one of the supreme magistrates as a supporter of the White party. The Blacks asked Pope Boniface to intervene, and he sent Charles of Valois to settle the conflict. In 1301 the Blacks, with the help of Charles took Florence and exiled those associated with the White party, including Dante. Over the remaining time of his life, Dante would stay at the homes of those he knew, possibly continuing his education (xviii). Dante felt that politics hindered man’s earthly happiness, and through his Comedy, he makes this argument apparent, suggesting solutions. He would later, in the course of his life, come to disagree with every political faction and look for solutions through scholasticism. Dante's subject was the entire world and the history of mankind. He used his own beliefs and education, combining religion and reason to explain the universe (xix). Dante disagreed with the papacy's striving for more secular power, and the belief that Emperors and Kings, as Christian rulers, fall under the power of the Pope. He argued that the two powers must be separate, believing that both derive their power directly from god to rule their respective domain, the secular world and the religious world. He saw this separation as a way to fulfill God's goals of both happiness in the earthly life and salvation for the coming celestial life (xxi). He believed that incooperation between the papacy and the empire created injustice and chaos. The majority of Dante’s blame fell on the Papacy, as he found the Church, particularly Boniface, to be greedy, arguing that the papacy's failure to focus on “spiritual guidance” resulted in the damnation of Christian followers (xxi). This is clear in Dante himself as politics has cast him out of Florence, and this is shown in Inferno, as Dante represents the path to salvation of every man that has been led astray.

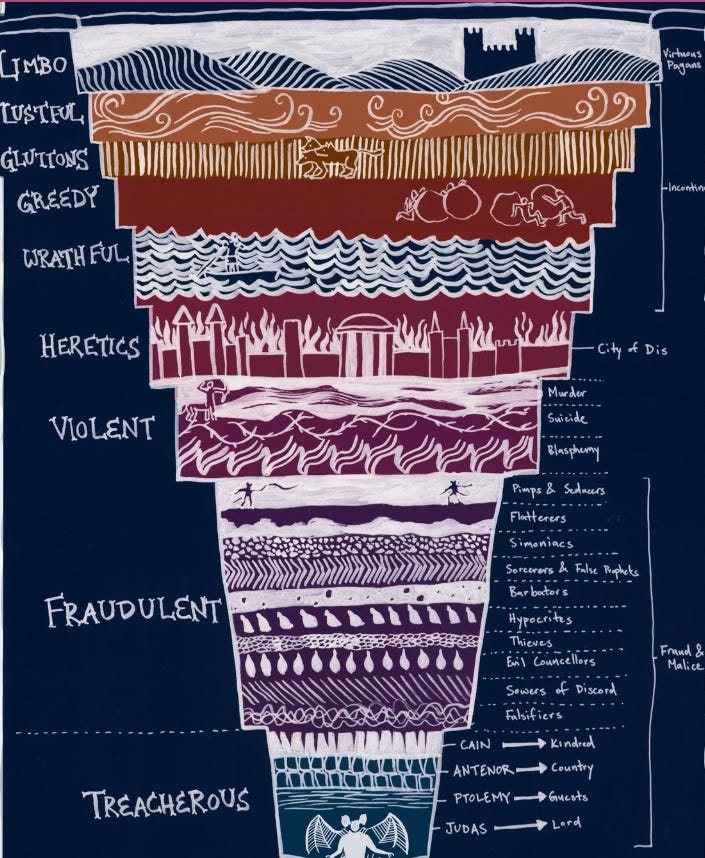

Politics appear again and again in Dante's Inferno. Dante not only placed his worst enemy, Boniface, in hell but also Pope Celestine V in the vestibule of hell where the opportunists reside (17). Celestine was elected as Pope in 1215 but abdicated the papacy to allow Boniface VII to ascend to power. Dante saw this as cowardly and blamed Celestine to an extent for allowing the corruption of the church that followed. Another face Dante recognizes in hell is that of Filippo Argenti, who was a political enemy of Dante (65). Farinata Uberti, who led the Ghibellines from 1239 till his death in 1264, was seen as an “arrogant ruler (81) and was declared a heretic in 1283, explaining why Dante placed him in circle six with the heretics. Along with him is the Cardinal of Ubaldini, who was said to have only cared for money and political gain. Dante specifically placed him with the heretics because he was believed to have said, “If I have a soul, I have lost it in the cause of the Ghibellines”. In circle eight, Dante finds Pope Nicholas III, who was Pope from 1277 to 1280, with the simoniacs. He explains that Boniface VIII will join him along with Clement V. All three Popes, Dante regards as corrupt and greedy.

During Dante’s time, catholicism played a major role in the way medieval people viewed the world. To them, everything in existence was created by the all-powerful and all-knowing God. This extended not only to the events that occur, but also to the social rank a person was born into. The existence of God was seen everywhere in things such as numerical symbolism. Dante’s Comedy is split into three parts, referring to the Holy Trinity. Specifically, Inferno reflects the “power of the Father” (xxii). Within Inferno, there are 99 cantos and the introduction, totalling 100, which is 10 times 10. This is significant because 10 was seen as the perfect number. After all, it is composed of the holy trinity times itself plus the unity of God (xxii). Medieval people saw their life on earth as “a vale of tears”. They believed that their existence on earth was intended to be a period of suffering as a means to prepare for the happiness of the afterlife (xiv).

Dante, however, disagreed with this view, preferring the idea that mankind should seek happiness in their “earthly paradise”, while preparing for the “celestial paradise” (xiv). In this way, Dante argues that mankind has foiled what he believed to be God's plan. Inferno is the place of the dead who have “rejected spiritual values” through various sins (xxiii). As reflected through Dante's criticism of the church, the High Middle Ages became increasingly interested in a more internal and emotional religious experience, and believed that the clergy was corrupt due to their involvement in politics. Dante’s character in the story of Inferno finds himself in the dark wood, representing his spiritual decline into sin as he has “strayed from the true way”. He sees the Mount of Joy with the sunlight of God shining down on it and attempts to journey there, however, he is stopped by three beasts representing different types of sin, who push him back toward the forest. But Virgil, the representation of human reason, appears to him to guide him away from error. He explains that Dante cannot take the easy path like Mount Joy, but rather embark on a long journey directly through hell and then through purgatory before reaching the “Light of God”.

His trek through hell is meant to represent the journey of man's soul towards heaven, and the recognition and rejection of sin. To recognize and reject sin, he must see it firsthand and learn of the suffering of others. In Dante’s theology, one can only be saved through Christ, and therefore, those born before him cannot go to Heaven, including his guide Virgil (9). Most shocking is that Dante explains in Canto III that Hell was created before man to punish the Angels that rebelled against God. This seems to be different from medieval doctrine that focused on the Original Sin that all humans share and was inherited from Adam. More confusing is that the God Dante describes in Inferno and which is well recognized in medieval religion, is all knowing, and therefore would have known man would sin (22-23).

Dante’s concept that man can descend further into hell and also ascend reflects the medieval belief that Dante shared of mankind’s inherent sinfulness and God’s mercy. Dante initially has to be scolded by Virgil for his pity for those in Hell and has to be reminded that all-knowing God has placed them there as a direct reflection of their sins. Throughout the book as they descend further into hell, Dante begins to recognize sin and reject it, and he feels less pity for those damned. Within the sixth circle, Dante finds the Heretics who denied the immortality of the soul. Medieval people believed this heresy caused the soul to die, and so Dante matches the punishment, having the heretics lie in hot iron tombs that will be sealed on judgement day, when the soul will die rather than ascend to heaven. He saw these heretics as blind, similar to the pagans. Homosexuals, known at the time as sodomites, were placed in the seventh circle of hell as medieval society saw homosexual relationships as violence against nature.

Dante’s education and subsequent opinions on both religion and politics stem largely from the revival of learning and intellectual systems that began in the 12th century. Population and economic growth were beginning to create a middle class, as governments also began to form. Cathedral schools were built to expand the extent of education and support teachers. Alongside this revival of learning came a renewed interest in the ancient texts that had been preserved in the monasteries, such as Aristotle and Dante’s favorite, Virgil. Eventually, in the early 12th century, universities such as Oxford emerged. Medieval Europe began to be influenced by classical texts as medicine became based on ancient sources and governments implemented elements of Roman law.

Medieval people believed that religious doctrine was the underlying knowledge, however, classical texts often disagreed with this doctrine. Scholasticism arose to solve this issue by comparing both Christian and Classical arguments to find a harmonious answer. Dante does exactly this in Inferno by explaining how Christian religious doctrine underlies every aspect of life, explaining hell in a way that reflects God’s wrath and forgiveness while also implementing classical human reason and science through Virgil and classical mythology. Dante believed you must submit yourself to human reason, and reflects this as many times in Inferno, Dante has to be carried by Virgil, for example, their descent through Satan's fur. Dante’s solution to this disconnect between Catholicism and classical human reason was to argue the normative idea of the earthly life as an intentional trial of suffering as the medieval church presented it, but rather the earthly paradise before the celestial paradise. He believed that this was God's intention and that the church had misinterpreted it.

One such example of scholasticism within Inferno lies in Dante’s understanding of Aeneas and the way he combines pagan beliefs and catholicism. Virgil explains that Aeneas was the son of Venus and a mortal man, and a prophecy held that he would create a royal line and become ruler of the world. He defeated Troy and, after a winding tale, visited the underworld where he learned his descendants would be the kings of the Roman Empire, including Romulus, Julius Caesar, and Augustus. But Dante expands on this by adding the Holy Roman Empire and the Holy Catholic Church. By doing so, he creates a narrative that connects the glory of Rome to the Medieval Holy Roman Empire as if it were God’s plan. Furthermore, classical pagan mythology is strewn throughout Inferno, particularly as beasts Dante must pass or the punishers of the damned. Dante’s hell is made up of the upper and lower hell, based on both Aristotle and Christian doctrine and symbolism. He reflected Aristotle in his three types of sin, incontinence, violence and beastiality, and fraud and malice. Incontinence was that of the upper hell, while the rest is seen as worse and therefore is left for the lower hell (89). Furthermore, medieval people believed in the Ptolemaic system that placed the earth at the center of the universe, therefore, Dante places the bottom of hell as the center of the earth (91).

Dante was far ahead of his time, seeming to argue for the separation of church and state, accessible education for the public, and claiming that man can and should search for happiness in his earthly life. He believed that as a result of the conflicts between the church and the Empire, both had neglected their duties to their people and created the strife and instability that led to sin. He made his disdain for the corrupt Popes and politicians apparent by placing them in their respective spaces in hell. Dante’s Inferno reflects the personal journey of mankind to salvation, finding the way out of the dark forest. This journey is a very emotional experience that reflects the changing spirituality of the High Middle Ages, which was promoted by Bernard of Clairvaux. At the end of Inferno, Dante depicts hell as cold. His explanation once again represents scholasticism as he presents both a religious reason, hell being furthest from the warmth of god, as well as a logical reason, the wind from Satan’s wings. Throughout Inferno, Dante references the political turmoil between the secular and Papal powers of his time, revealing the new need for a more internal connection to religion, and using scholasticism to challenge the normative ideas of Christian doctrine and society.

Thank you so much for reading! Please subscribe if you are interested in history and writing such as this!

this was sooo interesting!!! i loved the context about the politics at the time, so cool that Dante was naming names of politicians he envisioned to be in hell! you've really made me want to read Inferno now. another banger!! x

Thank you so much! You are so kind! I’m glad you enjoyed it and I definitely recommend the book! Many of the books have notes that will explain parts of the passage and some of the context which definitely helps!